The US Navy is stepping up negotiations for an autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) contract with Norway’s Kongsberg, a major benchmark in the rising number of navies using seabed mapping technologies to tighten control over rare earth elements.

A Kongsberg official at the maritime company’s site in Horten, Oslo, told Naval Technology that the US could join the twelve navies already using the company’s seabed mapping technology, including Australia, France, Italy, Norway, Poland and Spain.

In April, a US military delegation spent a week at Kongsberg’s site in Horten for demonstrations of the HUGIN AUV system – the latest signal of Washington’s intent to undermine China’s control over rare earth element supply chains.

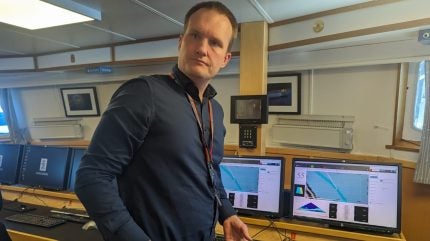

Funded by the US’ Defence Innovation Unit (DIU), the contract “could result in the [US] Navy acquiring HUGIN Endurance and HUGIN Superior deep-water AUV systems”, according to Espen Henriksen, Kongsberg Discovery’s Executive Vice-President for Unmanned Platforms.

What are the capabilities of Kongsberg’s AUVs?

Most HUGIN models can spend up to 15 days at sea, travelling distances up to 2,200km and diving to depths of 6,000 metres. Each AUV carries a wide array of sensors, including synthetic aperture sonars, multi-beam echo sounders, cameras, lasers, sub-bottom profilers and environmental sensors.

Henriksen clarified that while “close dialogue continues, at the moment no contract is signed” by the US Navy.

Kongsberg, which is majority-owned by the Norwegian government, has been awarded multiple contracts amid growth in the Scandinavian country’s defence market.

A prominent example is the National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile System (NASAMS), a joint venture between Norway’s Ministry of Defence (MoD), Kongsberg and US manufacturer RTX.

Norway’s MoD has earmarked a $7.6bn Nkr81bn) budget last year, which is forecast to increase to $9.2bn by 2028, according to GlobalData.

How do navies use seabed mapping?

The ocean’s seabeds contain two principal sources of rare earth elements.

The first is polymetallic nodules, which often contain copper, nickel, manganese, cobalt and rare earth minerals. The second is hydrothermal vents on the seafloor, which pump out rare-earth elements dissolved in their hot fluids.

From nuclear power and oil refining to electric vehicles and wind turbines, these elements are growing in strategic importance – and dwindling in abundance.

Researchers have been aware of the mineral richness contained within seabeds for more than a decade, but the Biden administration only released its plan to counteract Beijing’s dominance over rare earth element supply chains in 2021.

The use cases for AUVs extend beyond seafloor mapping. Use cases for these naval missions include Intelligence Preparation of the Operational Environment (IPoE), Mine Counter Measure (MCM) and Subsea and Seabed Warfare (SSW).

Monitoring seafloor and subsea infrastructure is another key application.

“We now look at the protection of the seabed and its critical infrastructure with entirely different eyes”, said Berit Floor Lund, Research Director at Kongsberg Discovery – referring to the Nord Stream incident in 2022, when underwater explosions damaged the pipelines which carry natural gas from Russia to Europe.

Outside of military applications, AUVs can also be used to monitor marine ecosystems and seabed damage inflicted by bottom trawling, but “more than one third of Kongsberg’s vehicles have gone into naval applications”, according to Berit Floor Lund, Research Director at Kongsberg Discovery.