"When Britannia ruled the waves and the sun never set on the British Empire, it was largely thanks to the pioneering Royal Navy hydrographic surveyors that charts could be produced to service her vast maritime business," says Lt Cdr AWJ Jenks MBE RN, who retired as a charge surveyor in 2011 after 37 years’ naval service and now lectures at Plymouth University Hydrographic Academy.

The story arguably starts back in 1681, when Capt. Grenville Collins was ordered to produce the first comprehensive survey of the British coast for Charles II. His command, the Royal Yacht Merlin, can, in the words of the late Lt Cdr Geoffrey B Mason, RN (Rtd), "be regarded as the first British warship dedicated to marine survey work as opposed to exploration". And thus began the Royal Navy’s long and distinguished hydrographic history.

Trust in God and an Admiralty chart

In the years to come, a maxim would develop – "trust in God and an Admiralty chart" – that has been familiar to generations of sailors ever since the very first one was published in 1801, and it still has resonance today – though things have, clearly, changed somewhat since the nineteenth century.

These days, the free exchange of data between member nations of the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) means that ‘Admiralty’ charts no longer depend solely on the navy’s input, and Britain’s hydrographic squadron is smaller too – though the reputation of neither has suffered in the transition.

Thanks to advances in technology, notably the advent of the multibeam echo sounder in the early 90s, ships are now capable of surveying large areas far more quickly and to a level of detail that would have been inconceivable 50 years ago. "Although RN survey ships are fewer than before, each one is vastly more capable than several of its predecessors combined," Jenks says.

Uncharted canyon

That capability was clearly demonstrated in February 2013 with the discovery of a previously uncharted Grand Canyon-style feature on the floor of the Red Sea. The discovery was made by HMS Enterprise in the course of her nine-month mission to improve knowledge of the waters east of Suez, which is due to end in summer 2013.

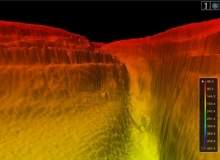

Detecting the massive underwater trench after her first ever visit to the Egyptian port of Safaga, some 250 miles south of Suez, the vessel’s state-of-the art multibeam echo sounder was then used to map the area, creating high-resolution 3D images and revealing a 250-metre deep canyon in the sea floor.

Whether they show the result of erosion by ancient rivers long before the Red Sea formed or a still evolving landscape cut by underwater currents, they are almost certainly, according to Enterprise CO, Cdr Derek Rae, "the closest that humans will ever get to gaze upon these truly impressive sights hundreds of metres beneath the surface".

These discoveries have a more immediately practical purpose, of course, than simply allowing an area of the seabed to be seen for the first time; to continue to be useful, charts are always in need of updating.

Growing demands

Until the launch of the SS Great Eastern in 1858, draughts of more than six metres were rare, and for the hundred years that followed, 15m was widely regarded as a maximum. Today’s ultra large crude carriers more than double that, and survey standards must constantly stay abreast of such changes. As Jenks explains, the demands on hydrography keep on growing.

"As the size and draught of merchant ships increases and submarines, ROVs and AUVs dive deeper, so the survey requirements become more exacting, rendering previous surveys inadequate." He says that cruise ship operators looking for new destinations where there has been little previous shipping activity – such as the polar regions – can also highlight the need to gather more up-to-date data for the charts.

The Royal Navy’s Hydrographic Squadron

At the forefront of that effort are the five ships of the Royal Navy’s Hydrographic Squadron – HM Ships Enterprise, her sister Echo, Protector, Scott (Britain’s only deep-water survey vessel and, at 13,500 tonnes, the fifth largest in the fleet) and Gleaner (the smallest vessel in the fleet) – and their crews of surveyors.

During the early decades of the 1800s, as Hydrographer of the Navy, Captain Thomas Hurd established the principle that ships deployed exclusively for hydrographic work should be manned by specialist officers. Today, 200 years on, it may seem obvious, but this then-revolutionary idea was to ensure that those who commanded survey ships were perfectly fitted to the task, and understood the unique demands of their role. The benefits of Hurd’s thinking persist today, with navy surveyors – both officers and ratings – being trained, alongside their foreign and commonwealth counterparts, at the Flag Officer Sea Training (FOST) Hydrographic, Meteorological and Oceanographic School in Devonport.

"One of the strengths of naval surveyors is that they crew their own survey vessels – there’s nothing like being a user of a product yourself to focus the mind when gathering data for future such charts and publications," Jenks says.

Piracy and terrorism

Charting the seas may have largely grown out of the nineteenth century’s relentless drive to expand trade, but the need to defend the global markets that it ultimately made possible means hydrography plays a pivotal role in addressing two of the pressing concerns of our own age – piracy and terrorism.

"A lot of the small groups operating in parts of the world today are obviously very clued-up on local knowledge, and with defence procurement cycles being the way they are, these guys are often as well equipped as national forces when it comes to electronics equipment – if not better. Cell phones, GPS and so on, it’s all available off the shelf, and they can get access to latest generation stuff very easily," says defence blogger Newton Hunter.

However, he says that conventional navies have a real advantage with their broader-based seamanship and a greater understanding of manoeuvrability, especially when it comes to larger vessels. "It’s all about core competencies. Somali pirates are always going to be a threat in the regional waters that they know – so to beat them, you have to know the waters even better. Same thing with gunrunners, smugglers and terrorists. In the end, you can’t out-sail good hydrographics."

With its pirates, reliance on sea routes and focus on trade, in some ways the 21st century seems little changed from the maritime issues back in 1819, when permission was first given for Admiralty charts to be sold to the Merchant Marine. It is small wonder, then, that both they – and the surveyors who produce them – continue to enjoy the mariner’s trust.

Related content

Echo Class Hydrographic / Oceanographic Survey Vessels, United Kingdom

The Royal Navy’s Echo Class hydrographic / oceanographic survey vessels (SVHOs) were introduced by Vosper Thornycroft.

The war against pirates – how navies are addressing evolving maritime threats

Despite high-tech naval vessels and countermeasures, piracy is on the increase and spreading its area of influence.

.gif)